When I was much younger, I had a rule of thumb that it’s possible to make a good film of a bad book but that films of good books are invariably bad. It’s not difficult to see why. The author has, presumably, chosen to use the techniques of prose fiction because they were best suited to the story s|he wanted to tell. To create a visual representation of, say, an epistolary novel or an unreliable first-person narrative is to accept the challenge of matching the author’s vision in a medium whose possibilities are quite different. The most obvious constraint is that of time: a good book simply contains too much to be translated into two hours’ viewing.

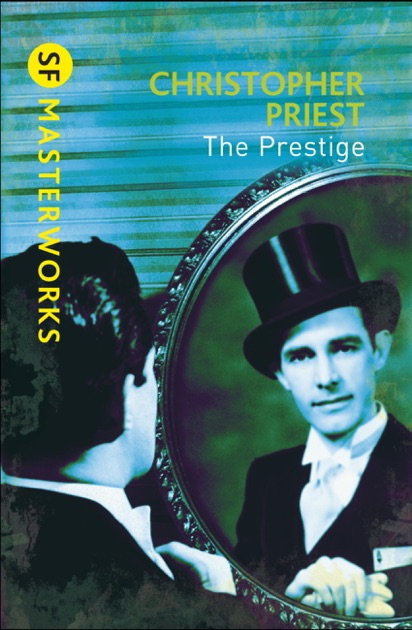

I’ve belatedly concluded that Christopher Nolan’s film of The Prestige is a good film. (I’ve disliked all his films except Following on first viewing. In some cases, notably Memento, I came to like and admire them only later.) Does that mean that Christopher Priest’s novel is a bad book? It is certainly a flawed one. But in some ways, it is a more interesting failure than Nolan’s successful film.

The main difference between film and book is in their themes. The film centres on the sacrifices an artist has to make. Total dedication is required, including the deception of loved ones as to the extent of the artist’s commitment. You have to live your act, as Borden tells his rival, Angier, in the film. It may be necessary to spend decades in character, at the expense of any kind of normal life.

This theme is hinted at in the novel too, but Priest’s protagonists don’t rise anywhere near the level of artists. They’re rather pathetic characters languishing in the grip of their obsessions. The book’s Borden shows the same commitment as his screen counterpart to the single-minded pursuit of his craft but his ultimate accomplishment is not really all that impressive. Angier makes a horrific sacrifice too, but it’s not as much a conscious choice as Borden’s (or as that of his counterpart in the film). Nolan makes the characters mirror each other to a far greater extent than Priest does.

Priest’s main theme is more out of the ordinary and therefore more interesting than Nolan’s. He creates a kind of secular ghost story — one without spirits. The characters are haunted (and haunting, in turn). Angier starts his career as a fake spiritualist, exploiting the recently bereaved. Of course, there is no “other side” from which the lately deceased can communicate with their loved ones. Priest explores the possibility that there might be ghosts and hauntings without the existence of spirits.

The story is told in a succession of first-person narratives (with a curious third-person interlude in the middle). A male descendant of Borden’s opens and closes the story, then we have Borden’s account (the dullness of which is the book’s main problem). This is followed by the narratives of Angier’s great-granddaughter and then Angier himself. The story gets much more exciting as it progresses and the ennuis of Borden’s part of the narrative fade from memory.

Nolan’s compression and streamlining of the story are impressive but I slightly regret not having had the opportunity to read the book without first seeing the film, superior though the latter is. Of course, if it hadn’t been for the film, I’d probably never have heard of the book.

Originally posted on Google+ by Art on 09-Aug-2017