Criticism, fiction and other writing

In the discussions of poetry by Andrew Marvell and William Empson that I’ve posted over the past few years, I have had to rely on scholarly editions of their poetry. In the case of Empson, I quoted from John Haffenden’s The Complete Poems of William Empson (Penguin, 2000) and for Marvell I used Nigel Smith’s The Poems of Andrew Marvell, revised edition, (Routledge, 2007). In each case, I found it necessary to replace the poetry quotations in my original draft/version of the post with the corresponding passages taken from the chosen edition. That was one of the factors that got me thinking (again) about scholarly editions of poetry.

For example, my original 1996 essay on Empson’s poetry quoted lines 11–12 of “Invitation to Juno” as

Could not Professor Charles Darwin

Graft annual upon perennial trees?

That version of line 11 is the one that appears in Empson’s Collected Poems (Chatto & Windus, 1955) — very nearly the ideal form of a “slim volume”, with a beautiful yellow dust jacket — that I had used while writing the essay. For online publication, I substituted the version of line 11 from Haffenden’s edition:

Did not once the adroit Darwin

Graft annual upon perennial trees?

According to Haffenden, Empson changed line 11 because he was dissatisfied with the inaccurate characterization of Darwin as a “Professor”. So, “the adroit Darwin” accords with authorial intention, albeit an intention that crystallized many years after initial publication of the poem. I think Empson’s change is an improvement in one way and a disimprovement in another. (Probably the latter on balance.) It certainly gave me pause on first reading, because of my familiarity with the “Professor” version of the line.

The first edition of Nigel Smith’s The Poems of Andrew Marvell appeared in 2003 in hardback and I used it extensively while working on my doctoral thesis. But by then I had already adopted the practice of quoting Marvell’s poetry from an earlier scholarly edition, and I continued to use the earlier edition for quotations throughout my thesis. This was Margoliouth’s The Poems and Letters of Andrew Marvell, 3rd ed. by Pierre Legouis with E. E. Duncan-Jones (OUP, 1971). This edition, though impeccable in most respects, was 30 years older, dating from a time when scholarship tended to be less obtrusive.

One of the examiners of my thesis pointed out to me that to quote from the earlier edition, now that Smith’s was established as the new standard, appeared eccentric and wilfully anachronistic on my part. I decided that for further publication I needed to replace the quotations from Legouis/Margoliouth with the corresponding passages from Smith. I did so without enthusiasm, but that is not to say that I don’t appreciate Smith’s contribution. I am not merely hugely indebted to the work of Haffenden and Smith, I am wholly in awe of it, to the point where I find myself in a position analogous to Marvell’s, when he acknowledged that he “must commend” Milton’s Paradise Lost:

… I am now convinced, and none will dare

Within thy labours to pretend a share.

Thou hast not missed one thought that could be fit,

And all that was improper dost omit:

So that no room is here for writers left,

But to detect their ignorance or theft.

…

Where couldst thou words of such a compass find?

Whence furnish such a vast expanse of mind? (“On … Paradise Lost”, ll. 25–30, 41–2)

Yet, overwhelmingly impressive though their work is, I suspect that if I had first encountered Empson’s or Marvell’s poetry in one of these editions I wouldn’t have been quite so keen to write about it. I still feel that the “natural habitat” of Empson’s poetry is 119 small octavo pages, rather than Haffenden’s 512 somewhat larger ones. Several times while lightly editing the Empson essay before posting it on the web, I caught myself wishing that I had the 1955 Collected Poems within easy reach.

In much the same way, I noticed many years ago a reluctance on my part to reread one of Marvell’s poems in its entirety. Instead, I’d open the volume to check a line, a reference or an argument. For a while, I thought this was just ennui resulting from overexposure. But I’ve often suspected that there may be more to it than that.

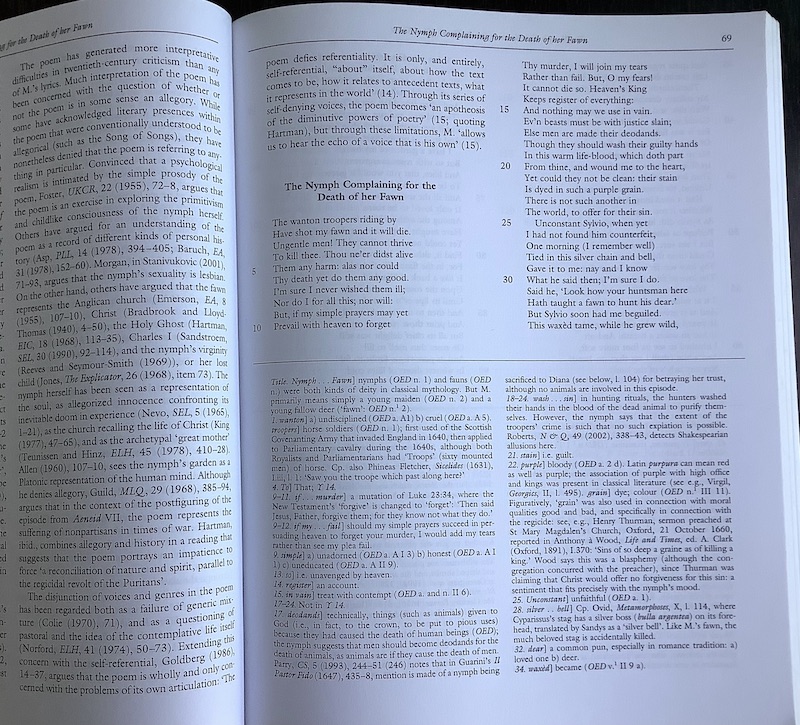

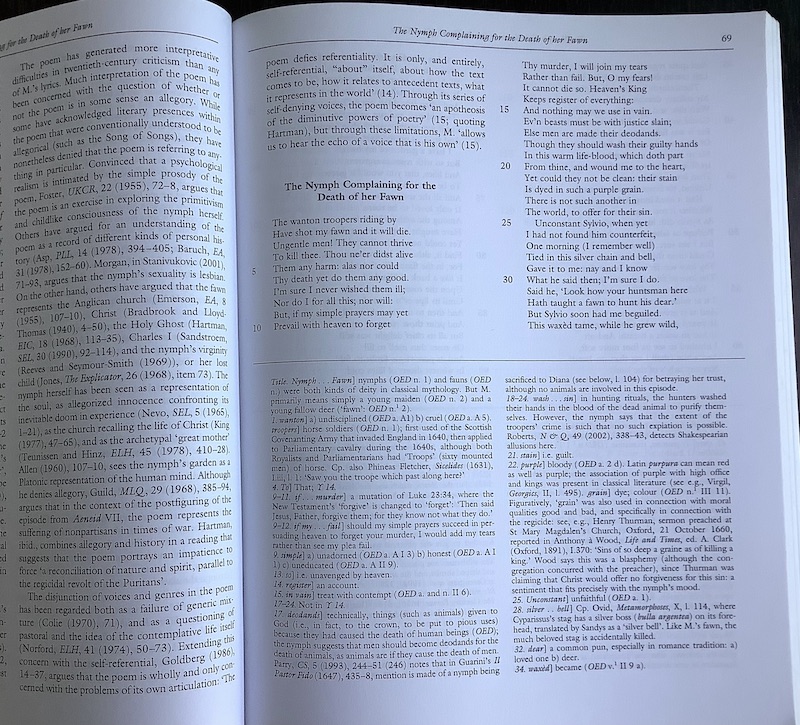

This is the opening from the Smith edition of one of my favourite poems, “The Nymph Complaining for the Death of her Fawn”. Without wishing to appear in the least ungrateful for Smith’s painstaking work, I can’t help feeling that Marvell’s lyric is a bit cramped or constrained by the weight of scholarship that surrounds it. If I were approaching “The Nymph Complaining” for the first time, I suspect that I’d find this presentation, with its dense context, just a little forbidding. And one of the problems with reading poetry is that even very small obstacles can derail an attempt to take it in.

This gives rise to a real dilemma. A mid seventeenth century poet like Marvell can appear deceptively modern: the twenty-first century reader is often at risk of mistaking the poet for our near-contemporary, and therefore misreading his work. I need to be periodically reminded that the culture of print publication, the system of censorship and “licensing”, the constitution of Parliament (of which Marvell was a member for the last 20 years of his life) and the meaning of the word “constitution” itself (to take just some of the more obvious examples) each had a different significance for Marvell than it may have for me.

Historical scholarship provides some protection against this kind of misinterpretation and is therefore indispensable. But I suggest we need a way to hide it so that it doesn’t make its presence felt too early in the reading process. One possibility would be to start reading the poetry from a popular edition (or, as I did with Marvell, from an earlier scholarly one). But the popular or outdated edition probably contains readings that have since been questioned or rejected, and will ignore the most recent discoveries.

Ideally, the reader and discusser of the poetry needs the most up-to-date text, but separated (to the extent it can be) from extraneous commentary and annotation. There are some obvious ways this could be achieved. Publishers might divide their scholarly editions into two volumes, one containing only the poetry, the other the scholarly apparatus. Depending on the needs of the reader, both volumes could be opened and read side by side, or one could be consulted at a time. Another possibility would be to produce just one volume, containing the “bare” text of the poetry, with the critical and scholarly material being made available online.

Some 20 years ago, I owned a large, thick paperback, The BeOS Bible by Scot Hacker. Purchasers of the printed book could get access to supplementary and updated material on the publisher’s website. As far as I remember, I didn’t make much use of the online material. I probably thought that the approach was something of a gimmick. Twenty years on, I think I may see a use for that approach.

Posted by Art on 22-Aug-2020.