Criticism, fiction and other writing

Correction: It seems that I was wrong in thinking that a barcode and printing details on the last page are an indication that the book was printed on demand. I took this from a BlueSky post by someone who seemed well informed. But it probably indicates merely that the book was printed digitally, not necessarily on demand. I now think that the Andrew Marvell Chronology in particular is probably not a PoD title. Apologies for the confusion and misinformation. I’m leaving this post up for the time being, but may rework it completely when I get time.

A few weeks ago, writer Joanne McNeil posted on BlueSky a warning that Amazon “will ship crummy print-on-demand copies of books when their stock runs out.” This post was the start of an informative thread that, among other things, tells us how to identify a book that has been printed on demand. The last page of the book will have a barcode at the bottom, with details of where the book was printed.

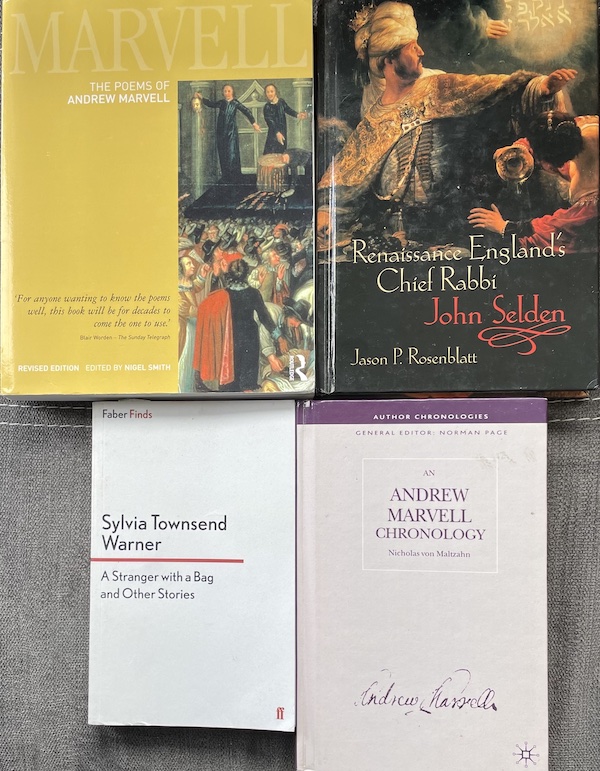

I had long suspected that one book in particular that I’d bought in the late 2000s was a print-on-demand copy. Now I was able to confirm the fact. The book is a hardback, an academic title from Oxford University Press: Jason P Rosenblatt’s Renaissance England’s Chief Rabbi: John Selden (2006). Sure enough, the last page has a barcode and says that the book was “Printed in the United Kingdom by Lightning Source UK Ltd.”

I thought that the reason I suspected that this was a print-on-demand book was that the print quality was a bit faint and indistinct, though the print was quite legible. Looking at it again now after a gap of more than 10 years — I last referred to the book in 2012, the year I submitted my thesis — the print quality doesn’t seem unusually poor, but I notice an italicized statement on the copyright page: “This book has been printed digitally and produced in a standard specification in order to ensure its continued availability”. When I first read that statement, I’d never heard of print-on-demand, a process I became aware of only in 2016. So, in 2012, I had no idea how to interpret the statement that the book had been printed digitally and produced in a standard specification. When I later learned that print-on-demand exists, I presumably remembered that there was a reason to think this book might be an example, but misremembered the reason.

At any rate, as I flick through the pages now, it doesn’t seem to me that the print quality is any worse than that of the typical recently published book. If I have reservations about quality, they relate to the binding rather than the print. I’ll say more about that below.

Armed with this new skill of being able to distinguish a print-on-demand book from a traditionally printed one, I soon discovered that I have a few books that I’d never have guessed had been produced that way. They are:

I also have the first edition of The Poems of Andrew Marvell in hardback (2003). This is not print-on-demand. I bought the revised edition while I was spending six months in France in 2015 and I didn’t have the hardback with me. I ordered it from Amazon (from whom I was still buying things in those far-off days). Nicholas von Maltzahn’s Marvell Chronology is the only one of these in hardback; the other two are paperback. There’s a note at the bottom of the Chronology’s copyright page: “Transferred to digital printing 2005”. Again, at the time I bought the book, probably no later than 2007, I didn’t know what this meant.

In none of the four books do I find the print quality less than acceptable. In the case of all but the Rosenblatt, I was surprised to learn that the books had been digitally printed. However, the bindings of the two hardbacks cause me a bit of concern. They both creak when the book is opened or shut and I worry that the pages will eventually start to become unglued. Irrespective of how a book is printed, I tend to think of hardbacks where the pages are not sewn as bad value and I try to avoid them. I remember when I bought the Chronology being slightly surprised at how relatively expensive it was, so I’m slightly annoyed at not having received for my money something more robustly bound. To be fair, it’s still holding together more than 15 years after I bought it; though again I’ve barely looked at it since 2012 and till yesterday not at all since 2015.

The Townsend Warner volume is part of the Faber Finds series, which (according to the thread referred to in the first paragraph above) consists entirely of print-on-demand books. Ironically, given that one of the declared aims of digital print is “to ensure its continued availability”, I couldn’t find a freshly printed copy and had to hunt for a secondhand one. It’s just occurred to me that Amazon could presumably have sold me a new copy but I didn’t look there.

On the basis of this tiny sample of books, I’m inclined to assume that print-on-demand will probably produce paperbacks of acceptable quality but that hardbacks are more of a gamble. That’s not to say that I think Joanne McNeil was wrong to complain about Amazon sending out “crummy” copies when they run out of regular stock. Clearly the colours on the cover of Amazon’s PoD copy are duller and less eye-catching than those on the copy supplied by the publisher. She also mentions that the paper quality is poorer. So I still think McNeil’s objection is a good reason not to buy books from Amazon.

Posted by Art on 31-Mar-2024.