Criticism, fiction and other writing

I’ve written before about how the limitations of ebooks — most of them arbitrarily imposed, but some inherent in the nature of the format — make them an inferior reading experience to printed books. For example, I’ve referred several times to Whit Stillman’s dissatisfaction with the display of footnotes in his Love & Friendship. Quite a few of the printed books I’ve read recently have relied on variations in font to indicate writing from different sources. In Liz Nugent’s Skin Deep , for example, the main character’s narrative is in a standard serif typeface while the interposed comments of various other characters — her adoptive father, her birth father’s best friend, her son’s childminder — are set in a sans one. I haven’t seen an ebook version of Skin Deep, but going by what I’ve seen in other cases, I’d be surprised if it respects this convention.

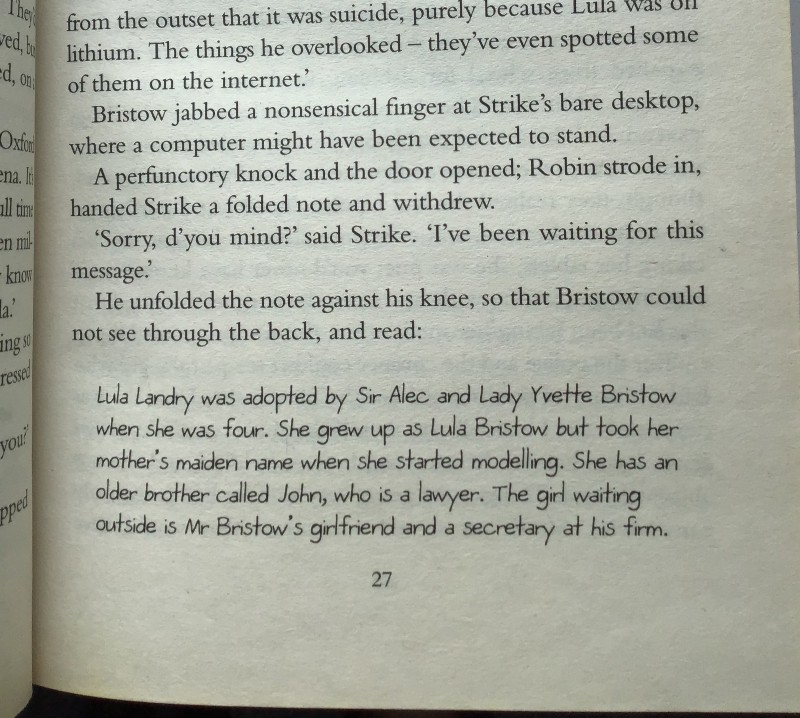

You might say that this is no big deal, that it’s more important that the reader be able to choose the font that best suits her than that the book designer’s, publisher’s, editor’s or author’s intentions be adhered to. I’m inclined to disagree. I was recently rereading Robert Galbraith’sThe Cuckoo’s Calling in paperback, having originally read it as an ebook, and I was taken aback to see that in places a cursive font had been used to replicate a handwritten note. On first reading, I’d had no suspicion that this was the case. Again, this isn’t a huge problem but it certainly contributes to a sense that the ebook is not quite the real thing, something of an afterthought.

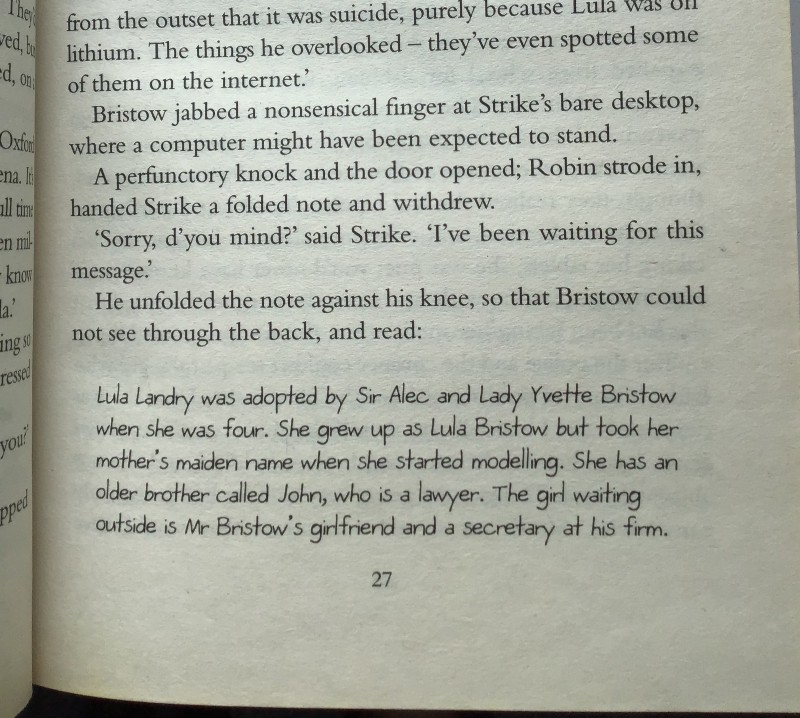

In the ebook, this note is rendered in italics. While this is admittedly an acceptable way to represent handwriting, there is no doubt that reading the ebook does not quite replicate the experience of reading the same book in print. Sophie Hannah’s A Game for All the Family is a more striking case. Early in the book we find several pages printed in a cursive font to represent the beginning of a story handwritten by the protagonist’s daughter. Here’s an example:

And here’s the same passage in the ebook:

The ebook version is easier to read, of course, but then the relative indecipherability of the printed version is part of the point, reflecting the central character’s struggle to make sense of what her daughter has written.

So in recent months I’ve been trying to find print copies of the books I want to read, instead of buying them from Apple Books or Kobo. I still buy ebooks occasionally but I’ve become cautious about what I buy in this format. The reason for my caution points at yet another way in which ebooks differ from print books. If you’ve read — or failed to finish — a physical book that you absolutely hated, and never want to be reminded that you once read, it’s a simple matter to give it away, take it to the charity shop or abandon it in your holiday hotel room. You never have to see it again. Good luck doing that with an ebook. Once you’ve bought a book from one of the main ebook sellers, it’s yours forever (or till the publisher decides to withdraw it).

In Apple Books, for example, you can remove the book from your device and you can hide it. Hiding means in theory that you never see it again but it remains in your iCloud library. This is analogous to putting all the old books you no longer want into a box and leaving it to be forgotten at the back of the attic or the garden shed, though it would be simpler and cleaner just to take the box to the charity shop. Seriously, have these Apple guys never heard of Marie Kondo?

Update 2 August 2019: I’ve posted some further thoughts on this subject under the title “How ebooks could become real books”.